Introduction

It’s 2013. I meet Ato at Kaneshie bus station, which is one of the main transport hubs in Ghana’s Accra region. Ato must be round about 50 years old. He is an imposing figure, short and stocky. He walks briskly around the station before returning to his starting point – a small booth at one of the station entrances, which he shares with a municipal employee. Like his three colleagues (who each work at one of the entrances), he is paid by one of the branches of the drivers’ union present at the station. He wears a blue uniform that is oddly reminiscent of military or police clothing. He seems to be the only one still in possession of his full uniform, though – the others are wearing only the jacket, trousers or cap.

Ato’s days are spent running around the station. He checks whether drivers leaving the station are wearing the right clothing. Vests and flip-flops are forbidden! He regularly stands at the exit of the station, inspecting the drivers’ footwear. One day, catching a driver wearing flip-flops at the wheel, Ato grabs the offending items and flings them into his booth. Standing in front of the driver’s vehicle, he issues a fine. The passers-by, drivers and street vendors who gather to watch the scene seem to hover between disbelief and hilarity – so much so that I wonder whether his overzealousness is due to my presence.

On other occasions, I follow Ato on his fast-paced tours of the station. It’s his job to keep the traffic flowing, he tells me. The traffic lanes in the station are narrow, there are a lot of vehicles, and the slightest manoeuvre can result in congestion. Ato walks fast, he’s sweating, he calls out to drivers, shouts, and bangs violently on minibus bonnets to make himself heard. If, as he passes between parked vehicles, he catches someone urinating, he can have them thrown out of the station or fined, he assures me.

“The Union Guards first appeared shortly after the Jerry John Rawlings coup d’état”

As we sit in his booth, Ato ends up telling me all about his career. He was trained in the USSR. I’m not sure I’ve understood correctly and find it difficult to believe, but he continues his story. He was recruited through a Muslim association to which he belonged at the time. A few hundred of them went to the USSR via this route. He then went to Libya to continue his military training – this was in the mid-1980s. There were soldiers from Malaysia and India at his camp, and the future dictator Charles Taylor was also there. Before leaving, Taylor offered everyone the opportunity of going to war with him, in Liberia. But Ato said no to this, and returned to Ghana. Back home, there were no jobs, so he decided to join the Union Guards – the military unit of the Ghana Private Road Transport Union, the main union in the transport sector. That’s where he got his uniform from. He had never been a driver before, but since he was already trained, a leading trade unionist recommended him. When he started, there were many Union Guards. Today, he is one of the few to have retained both some of his duties, and his uniform, following the changeover in 2001.

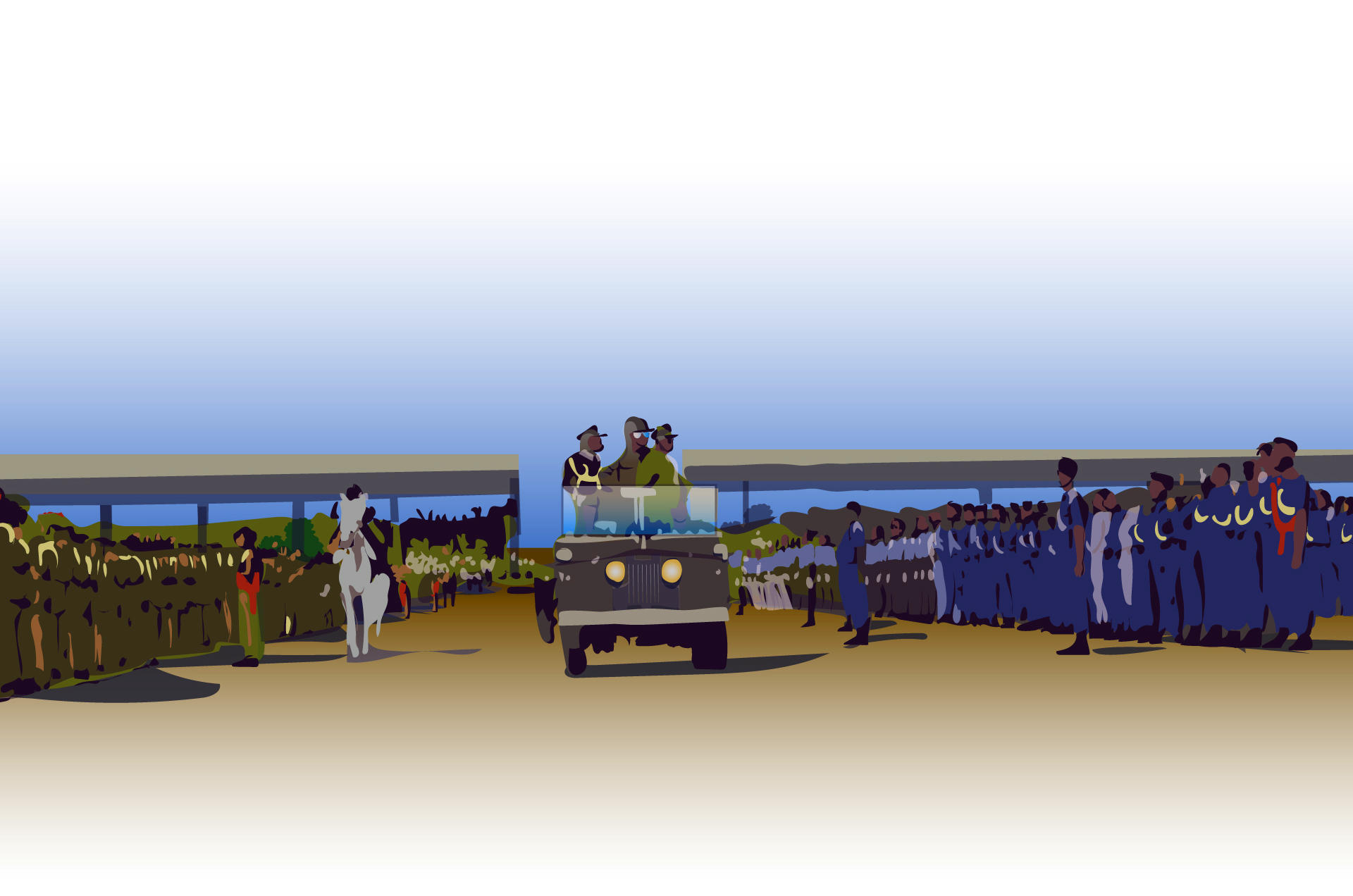

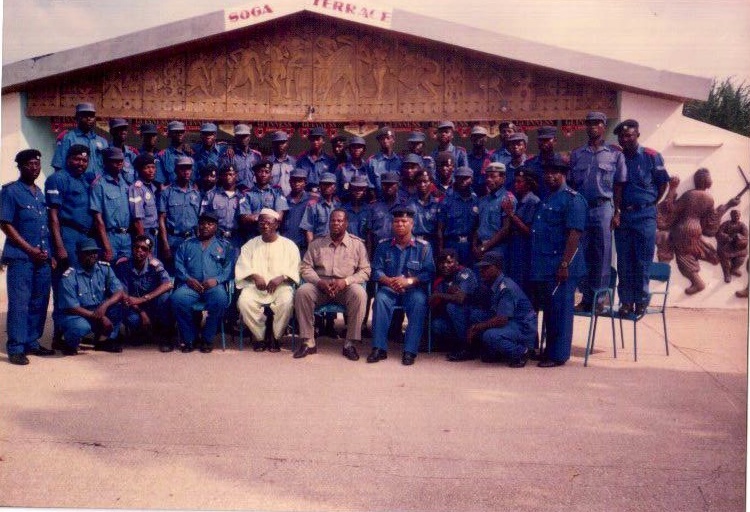

Ato is a Union Guard. These guards first appeared in the Ghanaian public space shortly after the Jerry John Rawlings coup d’état of the early 1980s. Initially they were posted to bus stations, then along the country’s roadsides as well, where they checked transport vehicles. At their peak, there were up to 200 Union Guards in the Accra area alone. On national holidays, they marched alongside the army, fire brigade and police.

This article revisits this little-known episode in contemporary Ghanaian history. It serves as a reminder that even the most codified forms of mobilisation – such as trade unionism – are subject to national historical contingencies. Rawlings’ military coup led to unprecedented militarisation of Ghana’s public space, and the Union Guards are a stark example of this. The emphasis on military attributes among guards was accompanied by the state’s delegation of public authority both at bus stations and along entire stretches of the road. In the case of the guards, the revolutionary context made the extent of these borrowings from military symbolism unprecedented, allowing this delegation to achieve a surprising degree of formality. It also made the existence of the Union Guards far more dependent on the changing political context.

Trade Unionism and The Coup

In the early 1980s, the road transport sector was an important part of the Ghanaian economy. Road transport, in public transport vehicles, was the main way in which people travelled around the country. Since the 1970s, however, the public image of the public transport driver has deteriorated – as has that of the transport sector as a whole. At the time of the coup d’état orchestrated by General J.J. Rawlings in 1982, transport and fuel shortages were among the biggest problems facing the revolutionary government. Improvements to this situation were to serve as a showcase for Rawlings, supposedly allowing him to illustrate his overarching project of modernising Ghanaian society. Control of this sector (and of the bus stations from which the traffic is organised) was therefore a priority.

“Since his first attempted coup in 1979, Rawlings supporters had joined the union”

The Ghana Private Road Transport Union (GPRTU) was the main union for the sector. Embedded in railway stations, its local branches were central to the strategy of the Provisional National Defence Council (the revolutionary government), which could count on a significant level of pre-agreed support from within the trade union movement. Since his first attempted coup in 1979, Rawlings supporters had joined the union. And since 1981, following an internal smear campaign against its leaders, they had even infiltrated the GPRTU management committee. In 1982, following the second coup and effective rule by Rawlings, his supporters were officially appointed to head the union. Soon after the coup, leaders of local union cells at bus stations around the country were offered government-sponsored management training. These training courses went hand in hand with the establishment of Workers’ Defence Committees – both at railway stations and more broadly across every sphere of society – followed by Committees for the Defence of the Revolution, which were intended to draw supporters of the revolution together.

From Bus Stations to Roads

In this context, a formerly local union initiative now extended to the national level. The Union Guards first emerged in the Ashanti region in the 1970s. They were set up by a trade unionist who had already headed a regional branch of the union prior to the takeover by Rawlings supporters in the early 1980s. In those days, there were no more than a dozen guards; they served only as bodyguards for the union’s regional representatives and were trained by a retired military officer who had become head of a local union cell that was based at a railway station in the capital of the Ashanti region.

From 1983, the initiative was taken up nationwide. The official year of establishment of the Union Guards is noteworthy; it happened alongside a broader movement towards militarisation of the various civil society organisations supporting the revolutionary regime. The movement was favoured by a prevailing climate of tension in the wake of a series of armed attacks against the still-fragile regime. The general secretary of the union personally informed the police and the army of the establishment of this new body. He enjoyed the support of some members of the government on this matter, in which the challenge lay in making the resulting body known to the various strata of the civil service, so as to impose it within the administrative order. It is however unlikely that this concern for publicity was a one-way street; the General Secretary of the GPRTU probably also used the Union Guards as a means of consolidating his own position within the hierarchy of the revolutionary organisation.

This upscaling went hand in hand with the extension of the guards’ mission. Now much more than just bodyguards to union executives, they were also guarantors of law and order at bus stations. The initial aim was to select five people from among those workers responsible for registering and loading vehicles at the stations, and provide them with three months’ training.

Up until the early 1990s, the conditions of this delegation of public authority to the guards were clarified and extended through a series of circulars explicitly stating that the ‘GPRTU is recognised by the government as the sole controlling organisation, regulating the movement and operations of all vehicles within bus stations’.1 The union thus became the “government’s legal agent, responsible for collecting everyday taxes for all commercial vehicles”.

The powers conferred upon the GPRTU allowed it to combine the collection of union taxes with those of the state. The union then paid the state’s share to the metropolitan assemblies, which continued ownership of the stations. In 1992, in a context of political liberalisation, the legal status of the guards was strengthened once again – this time by law, rather than by simple circular. The new law gave authorised guards to intervene on the road, rather than only at stations. It extended the scope of their activity to cover a number of road traffic offences, now enforceable against anyone driving a commercial vehicle.

Recruitment

“Having several Union Guards within its ranks was a sign of prosperity”

The extension of guards’ prerogatives went alongside the increase in their numbers. Guard recruitment tended to favour workers from the transport sector – such as existing drivers, former drivers and customer recruiters. Because of their familiarity with the driver’s role, guards were reputedly more effective in cracking down on offences committed by transport professionals. However, as a result of competition between the different echelons of the union, the recruitment of guards gradually diversified until it extended beyond the profession.

The recruitment of Union Guards was an issue within the union. Since local branches of the union were responsible for paying their own guards, having several Union Guards within its ranks was a sign of prosperity. Given the demanding nature of their training, the presence of guards also ensured the availability of high quality personnel. The presence of guards also commanded respect from other union units active within bus stations.

This recruitment drive opened up a second route into the Union Guards that was beyond the corporation – namely through union leadership networks. Several dozen people thus joined the ranks of the Union Guards – sometimes coming directly from the Revolutionary Defence Committees and having benefited, like Ato, from military training in East Germany or Libya. This competitive aspect also explains the presence of women among the guards – even though the profession of driver and all the local teams of the union were exclusively male.

Differences between recruitment channels were mitigated by longer training (from three months to six-to-nine months from the mid-1980s onwards), including for those having already passed through Libyan and/or East German training camps. This training wa0s carried out on army premises under the joint supervision of an army officer and a Union Guards officer. The accounts gathered seem to point to this moment as an important one in the creation of an esprit de corps. The difficulty of the training led to many departures and seemed, for those who stayed the course, to mark a real break with their former life. In addition to physical exercise, recruits were taught military-style posture and marching, as well as such values as uniform compliance and duty.

Dual Control

At their peak in the 1990s, Union Guards were under the joint control of the union and the authorities. People arrested by guards were taken to the nearest police station, though guards were also required to report such arrests to the union’s regional representative. Every two weeks, the police passed the list of people arrested by the guards to the trade union; this list also showed the charges ultimately brought against these people. In return, the union’s regional representative had to provide the police with a fortnightly summary of actions taken by the Union Guards, together with a list of those arrested.

This dual control extended to the collection of commercial vehicle taxes, which was carried out by the guards on behalf of both the state and their union. All drivers of commercial vehicles had to pay the daily state tax plus the union fee to all guards without exception, before leaving the bus station. The coupling of these two payments cleverly allowed the union to maintain its monopoly, even though trade union pluralism was allowed.

“The military training served as the basis for a distinction between guards and other station workers. Together with the uniform, this training was used to justify their hierarchical superiority”

The various formal rules that governed cooperation between the union and the police seem to imply a horizontal relationship between the union and the civil service. This should not, however prevent us from thinking about the asymmetrical relations that developed in the grey area between the guards and the rest of the union organisation, nor indeed between the guards and the rest of the civil service on the other. These relations varied, depending in particular on how guards were recruited and assigned. We can however attempt to describe it in broad strokes.

The above-mentioned military training seems to have served as the basis for a distinction between guards and other station workers (from which a significant proportion of the guards came). Together with the uniform, this training was used to justify their hierarchical superiority over rank and file members of the union. This made the Union Guards a prestigious entity within the organisation – albeit one that was kept separate, answering to a command that ran parallel to the rest of the union’s bureaucracy. This last was made up of the highest-ranking members of the Union Guards, most of whom came from either the Revolutionary Defence Committees or the contingent having received military training in East Germany.

The guards, however, appeared subordinate in their relationship with the police. They may have had a uniform – but they were not armed. They had very little autonomy in choosing the location or frequency of their roadblocks. Given the guards’ proximity to both the transport arena and the trade union that employed them, one might also imagine that their actions towards drivers within the police force took place in a climate of suspicion.

The End of Exception

The formal integration of the Union Guards into the civil service left the body of guards extremely vulnerable to political change. When the regime came to an end in the early 2000s with the definitive closure of the historic revolutionary moment, their activities came to a halt. With the changeover and the arrival in power of John Kufuor, the guards fell victim to the new president’s obvious desire to rid himself of the revolutionary legacy.

The 1992 law allowing guards to inspect commercial vehicles outside stations, and coupling the levy to the union’s collection was repealed. Tax collection was now the responsibility of Treasury representatives located at railway stations. As a result, union income fell drastically – as did the number of shifts.

This change left room for an uneven situation. Some guards joined the army, the municipal police or the fire brigade. Because it allowed careers straddling the union and the civil service, the guards’ official status facilitated their disaggregation. Others abandoned their uniforms and went back to being simple touts, while continuing to enjoy greater prestige within stations because of their past positions as guards. Ato belongs to a group of employees that has kept the uniform, and continues to be paid by union branches within stations to be in charge of security and traffic. The institution’s decline is however discernible in their uniforms – which now have to be maintained at employees’ own expense – and are mostly partially mismatched, or patched.

Things are different in the Ashanti region where the initiative first began in the 1970s, and where the regional guard contingent remains active. This difference can be explained in part by the high level of income from union dues in this particular region, which is considered a regional crossroads. At the time of my research in 2013, guards were providing security in the immediate vicinity of the station surrounding the building in which the GPRTU regional representation was housed. They were also responsible for stewardship of the union’s executive offices on the floors. Nonetheless, they continued to be involved in roadside checks at various locations in the city under the direct supervision of the municipal police – to whom they served as an auxiliary force for traffic control. This cooperation, however, was continuing outside of any legal framework – and without any fines or taxes being levied.

Conclusion

The history of the guards echoes many situations in which the state delegates part of its authority to organisations not bearing the state label. The extreme militarisation of the guards’ action, and the fact that this delegation was for a long time framed by law, nevertheless confer an unusual character on their story – even to those familiar with these ambivalent situations in which the boundaries between ‘state’ and ‘society’ are blurred.

Through their training, the guards had incorporated a state ethos. They carried out checks, collected taxes and imposed fines – and in so doing, performed functions ordinarily reserved for the state – or so we tend to believe. Since they reported directly to the police, and were trained by the army, they were (in some respects) part of the administrative hierarchy. Yet they were also part of a trade union.

These attributes contrast with the brutal disintegration of this body, following the first political changeover after the 2001 revolution. Even though the Union Guards had all the trappings of a solid institution, fully integrated to the administrative millefeuille, they seemed to dissolve with disconcerting speed. What appeared at first sight paradoxical ends up calling our presuppositions into question all the more deeply. Counter-intuitively, this suggests that the most formal modes of public authority delegation are not always the most sustainable, precisely because of their greater vulnerability to changes in the political environment.

This text was written for the Syndicalisme au Quotidien en Afrique (Syndiquaf) project. For a comparison between Ghana and Senegal on this subject see Cissokho, Sidy. “Être officiel ou faire officiel ? Sur deux styles de barrages routiers en Afrique de l’Ouest (Ghana/ Sénégal)”, Critique internationale, Vol. 83, N° 2, 2019, p. 167-189.

Notes

- Circular issued by the Minister of Local Government and addressed to the entire civil service, as well as to leaders of the other transport unions, 1989. GPRTU private archive ↩︎